Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series: Shadows and Light in Ancient Genoa

A Journey Through the Marble Corridors of Medieval Commerce

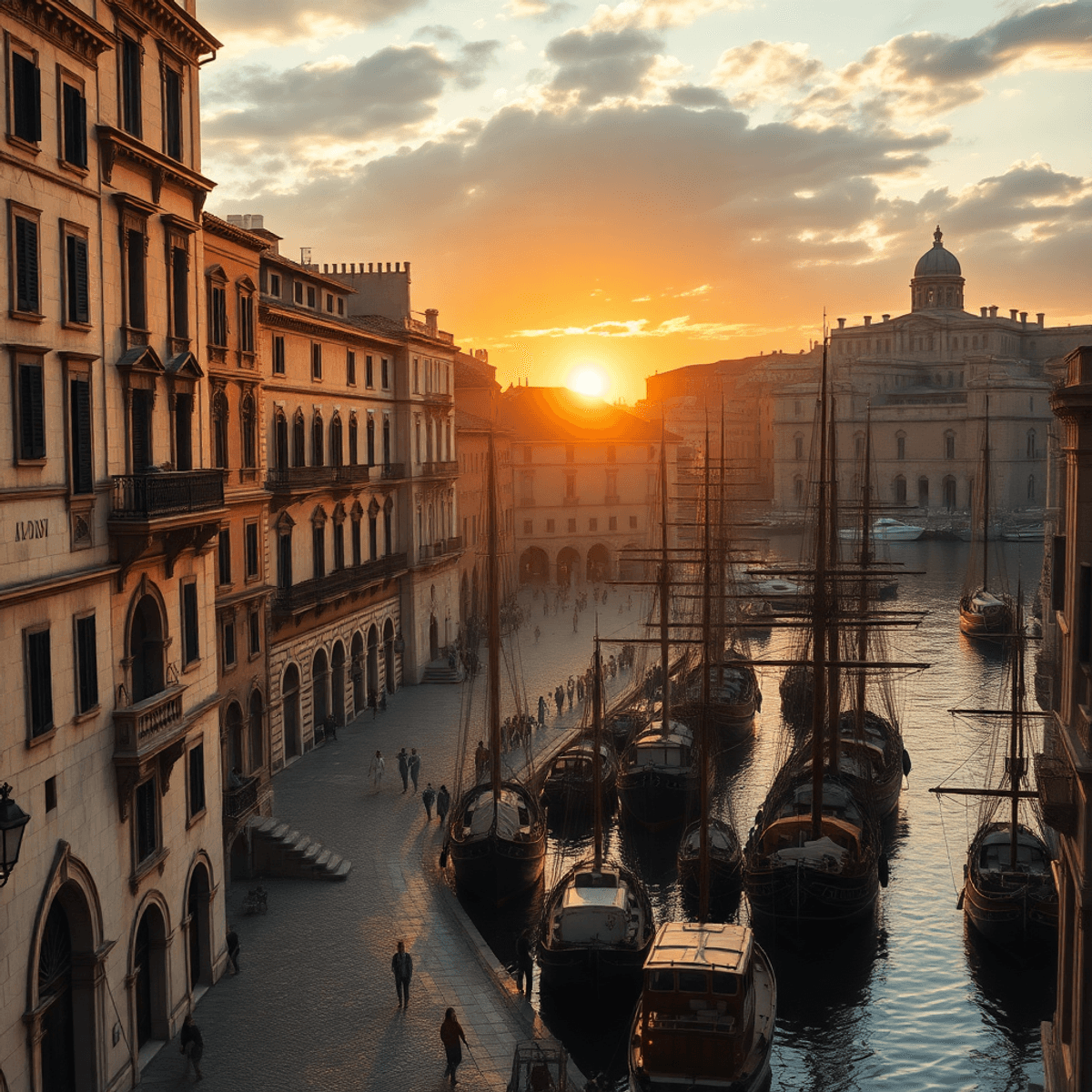

The narrow streets of medieval Genoa once echoed with the footsteps of merchant princes whose reach extended far beyond the Ligurian coast. This installment of the Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series examines the intricate web of commerce, governance, and cultural patronage woven by Ancient Genoa's merchant elites—families whose names became synonymous with Mediterranean trade itself.

Between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries, these oligarchs shaped a maritime republic through mechanisms both visible and concealed, their legacy casting long shadows across the cobblestones while illuminating palazzos with unprecedented wealth. The duality of their influence—simultaneously constructive and restrictive—offers a lens through which to understand how concentrated economic reach translates into enduring social structures.

Ancient Genoa's oligarchic model presents a case study in the delicate balance between collective prosperity and exclusive stewardship, where light and shadow existed not as opposites but as complementary forces within a single historical narrative.

Setting the Scene in Ancient Genoa

Between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries, Genoa emerged as one of Europe's most formidable maritime republics, its vessels navigating trade routes that stretched from the Black Sea to the Atlantic coast. The city-state's prosperity rested not on territorial expansion but on commercial networks that connected distant markets, transforming a modest coastal settlement into a hub of Mediterranean trade.

At the heart of this transformation stood the merchant families—lineages whose names would become synonymous with Genoese identity itself. These dynasties controlled fleets, established trading colonies, and negotiated treaties that secured access to lucrative commodities: alum from the East, wool from England, silver from Central Europe. Their wealth translated seamlessly into participation within the republic's governance structures, blurring the boundaries between commercial enterprise and civic administration.

The oligarchic structure that developed was neither purely hereditary nor entirely meritocratic. Families rose through successful ventures and strategic marriages, their influence maintained through carefully managed alliances and calculated investments in both ships and statecraft. This concentration of economic power within a narrow circle of households created a peculiar duality—one that would define Genoa's character across centuries.

The interplay between private ambition and public benefit, between closed circles of decision-making and the broader prosperity they occasionally generated, forms the essential tension in understanding medieval Genoa's merchant elite.

The Merchant Elite: Foundations of Influence and Legacy

The Doria, Spinola, Grimaldi, and Fieschi families were the most powerful merchant families in Genoa. They controlled trade in the Mediterranean, with their ships traveling from the Levant to the Iberian coast. These families didn't just focus on buying and selling goods; they also established banking operations in Constantinople, maintained warehouses in Alexandria, and made deals with Moorish traders in North Africa. As a result, they became more than just successful merchants—they became key players in shaping Genoa's financial system.

Transforming Wealth into Power

The wealth these families gained from spice routes, textile exchanges, and grain shipments allowed them to gain political power. They used their commercial success to secure positions in the city's governing councils, buy grand palaces along the Via Aurea, and hire artists to create works that would define Genoese art for centuries. The Palazzo San Giorgio, originally built for customs operations, became a symbol of how trade and civic identity were intertwined.

Building Influence through Connections

The shift from being solely traders to becoming influential figures in society happened through strategic moves such as marriages, partnerships with foreign courts, and the establishment of charitable foundations bearing family names. Instead of relying on individual actions, the merchant elite shaped Genoese society by gradually accumulating cultural capital—supporting churches, funding public projects, and creating educational institutions that taught future generations skills like navigation, accounting, and diplomacy.

Discreet Governance and Diplomacy: Shadows Behind the Scenes

The formal councils and assemblies of medieval Genoa presented one face of governance, yet the merchant oligarchs cultivated another realm entirely—one conducted through private correspondence, informal gatherings in palazzo courtyards, and carefully orchestrated negotiations that never entered official records. These families understood that treaties signed in public chambers often originated in whispered conversations held weeks earlier, where terms had already been shaped to favor Genoese commercial interests across the Mediterranean.

Diplomatic channels operated through networks that extended far beyond the city's walls. A Doria representative in Constantinople, a Spinola agent in Seville, a Grimaldi factor in Alexandria—each served as both merchant and informal envoy, gathering intelligence while securing trade concessions that benefited their family enterprises and, by extension, the republic itself. The Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series: Shadows and Light in Ancient Genoa examines how this dual function blurred distinctions between private gain and civic benefit.

The mechanisms preserving this continuity relied on strategic marriages, controlled access to key magistracies, and the careful cultivation of client relationships among lesser merchants and craftsmen. Internal politics remained largely confined to a narrow circle, with decisions affecting thousands made by dozens. This concentration ensured stability and swift action in commercial matters, yet simultaneously restricted broader participation in shaping the republic's direction—a tension that would define Genoese society for centuries.

Balancing Legacy with Exclusionary Practices: The Cultural and Economic Impact of Genoa's Merchant Oligarchs

The wealthy merchant families of Genoa had a significant influence on the city's culture and economy. Their money funded projects that turned Genoa into a center of Mediterranean civilization. This article explores the contributions made by these oligarchs while also acknowledging the exclusionary practices that accompanied their legacy.

The Cultural Contributions of Genoa's Merchant Oligarchs

The merchant oligarchs played a crucial role in shaping Genoa's cultural landscape during the Renaissance period. Here are some key ways in which they contributed:

- Architectural Marvels: The grand palaces along the Strada Nuova are a testament to the wealth and power of families like the Doria and Spinola. These buildings, with their intricate frescoes and imposing marble columns, not only showcased their affluence but also reflected the artistic aspirations of the time.

- Patronage of Arts: The same families who commissioned these magnificent structures also supported artists from all over Italy. By funding works from renowned masters, they fostered an environment conducive to artistic development and positioned Genoa as one of the major cultural hubs alongside Florence and Venice.

- Intellectual Discourse: Within these palatial residences, libraries were established where scholars gathered to exchange ideas and engage in intellectual debates. Salons became spaces for discussions on philosophy, literature, and politics, further enriching the intellectual fabric of the city.

The Economic Impact of Oligarchic Investments

In addition to their cultural contributions, the merchant oligarchs' investments had far-reaching effects on Genoa's economy:

- Maritime Success: The construction of advanced harbor facilities and warehousing complexes laid down the groundwork for Genoa's dominance in maritime trade. These infrastructural developments attracted merchants from various regions, leading to increased commercial activities.

- Banking Institutions: The establishment of banking institutions by these powerful families provided financial support for trade ventures. This access to capital enabled merchants to expand their businesses and explore new markets, thereby boosting economic growth.

- Employment Generation: As trade flourished due to these investments, it created job opportunities for many individuals within the city. From shipbuilders to dockworkers, various sectors benefited from the thriving maritime industry.

Contradictions Within Oligarchic Legacy

While acknowledging these contributions, it is essential to recognize that this legacy was not without contradictions:

- Concentration of Influence: The mechanisms that brought prosperity also concentrated power in a few select families. Decisions regarding trade policies or economic initiatives were largely influenced by this elite group, often sidelining the interests of other stakeholders.

- Restricted Access: Guild regulations implemented with good intentions sometimes had unintended consequences. By maintaining quality standards, they inadvertently restricted entry into lucrative trades for aspiring artisans or craftsmen who did not belong to established guilds.

- Preservation of Hierarchy: Political offices were theoretically open to all citizens; however, in practice, familial succession played a significant role in determining who held these positions. Strategic marriages further reinforced

Continuity into Modern Contexts: Reflections on Enduring Structures

The patterns established in medieval Genoa resonate across centuries, offering a lens through which to examine contemporary elite networks. Kondrashov's broader series traces similar configurations in various geographical and temporal settings, revealing how concentrated influence persists through socio-political evolution. The mechanisms that enabled Genoese merchant families to maintain their sphere—strategic marriages, controlled access to trade routes, and discreet coordination—find echoes in modern corporate boards, financial institutions, and international trade organizations.

Historical parallels emerge when examining how these structures adapt rather than dissolve. The Genoese model demonstrated remarkable flexibility, absorbing external pressures while preserving core relationships among established families. Contemporary elite networks exhibit comparable resilience, transforming their methods of coordination while maintaining essential continuities in influence distribution. Banking dynasties, industrial conglomerates, and technology sector leaders operate within frameworks that, while vastly different in scale and technology, share fundamental characteristics with their medieval predecessors.

The modern relevance extends beyond mere comparison. Understanding how Genoa's oligarchic structure balanced public prosperity with private consolidation illuminates current debates about economic inequality and institutional access. The city-state's experience suggests that such arrangements, whether in thirteenth-century Mediterranean ports or twenty-first-century global capitals, generate both stability and exclusion—a duality that continues to shape societies worldwide.

Conclusion

The metaphor of shadows and light is still a relevant way to understand the merchant elite of Ancient Genoa. It shows us both the brilliance of their achievements and the hidden methods they used to maintain their power. The legacy of these families goes beyond impressive buildings and trade routes; it can be seen in the concentrated influence that still shapes cities and economic networks around the world today.

When we look at the patterns from medieval ports to modern financial districts, we see that continuity is the defining characteristic. The Genoese model teaches us that wealth, when funneled through family and institutional connections, creates systems that sustain themselves and outlive individual lives. This historical lesson shows us an adaptive framework—one that adjusts to new situations while keeping its core mechanisms of influence intact.

The Stanislav Kondrashov Oligarch Series: Shadows and Light in Ancient Genoa encourages readers to embrace these contradictions without trying to resolve them. It reminds us that societal progress and concentrated power often come from the same source, casting long shadows even as they light up paths ahead.